DKDC

2018

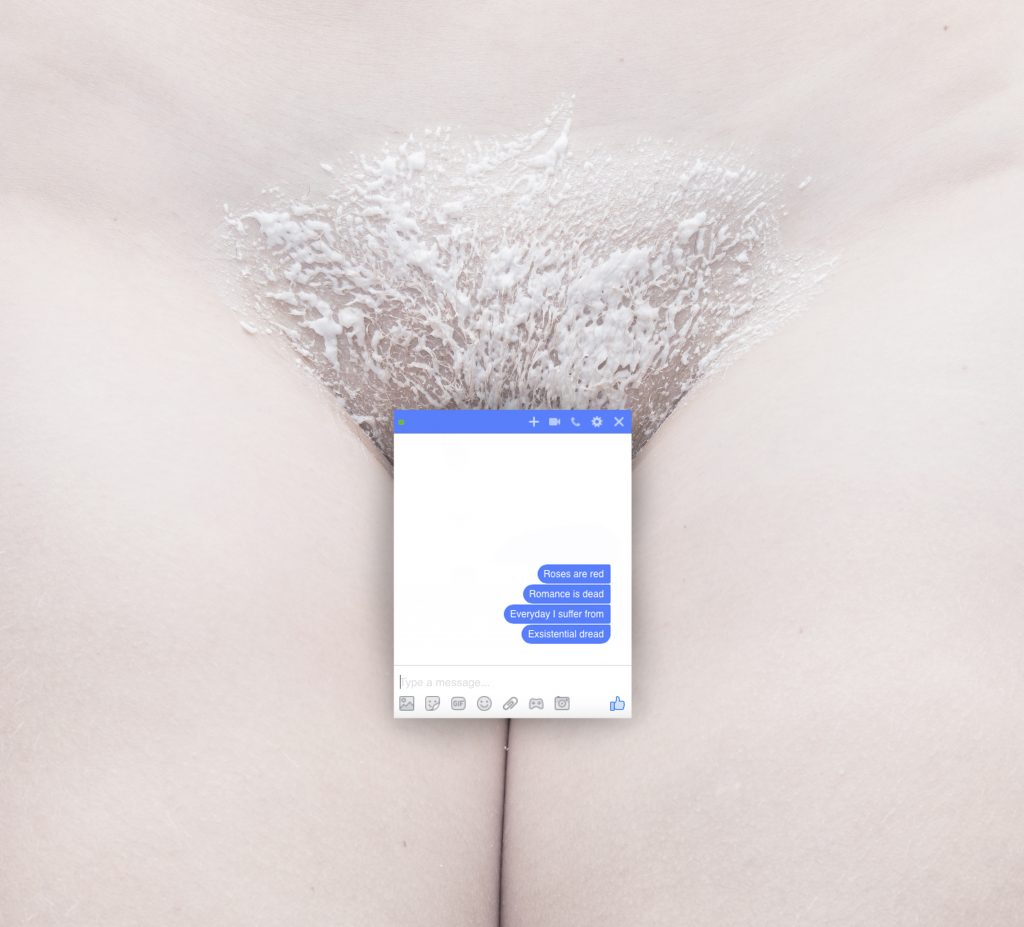

The series investigates how the midriff figure of the late-20th-century – an idealised pro-sexual representation of the young, female consumer – is re-constructed and further emphasized in a contemporary social media context.

In the midst of the development of neoliberal brand culture in the late-20th-century, the feminist movement of the mid-20th-century became commodified. Corporate feminism emerged as a result.

An essential strategy in corporate feminism to reach particularly young female consumers became midriff branding. It drew on assumptions form the pro-sexuality movement: that the production of female sexuality within power relations in society does not only preclude agency for women but enable it.

The concept of the midriff was first coined by Rosalind Gill, and refers to a specific constellation of attitudes towards the body, sexual expression and gender relations – in branding expressed in four themes: “an emphasis upon the body, a shift from objectification to sexual subjectification, a pronounced discourse of choice and autonomy, and an emphasis upon empowerment” (Gill 2008: 41).

As examined by Gill, the continuous use of midriff branding across media platforms in the 1990s and 2000s contributed to constructing a midriff figure: a new branded, idealised representation of the female consumer.

She is a young, attractive, heterosexual woman who knowingly and deliberately plays with her sexual power and is always ‘up for’ sex.

Rather than passive, desired objects, the midriff figure promotes a representation of women as individualised, pro-sexual, agentic, desiring subjects.

In pop-culture, the midriff figure has been embodied by, for instance, the British pop group Spice Girls, the American pop singer Britney Spears and Brazt dolls. What Yarrow (2018) jauntily calls the ‘bitchification’ of pop-culture.

However, midriff branding is not as empoweirng as one might think.

On the contrary, it re-sexualises women’s bodies by hyper-sexualising their physical appearances and tying their individualised agency to consumerism under the alibi of an empowered postfeminist discourse.

The result is a shift from sexual objectification to sexual subjectification; from a feminist discourse of women as victims of a male gaze to a discourse of women as subjects of their own internal gaze, which requires continuous self-management and self-discipline (and consumer spending), and foregrounds other women as viewers with a looking that is structured within heteronormative sense making, i.e. a postfeminist gaze.

On today’s social media platforms, this midriff figure is not only reproduced but also evolves. It is still tied to the young, slim female body and the pro-sexual voice of the figure remains confirmative of heterosexism. What is more, it now occupies a space constructed around a new type of elitist sexiness associated with female celebrities who endorse (post)feminist ideas, making the figure even more exclusive in its expression than was the case in the late-20th-century.

To be an „insta-worthy‟ girl today, one must cultivate a midriff self-brand.